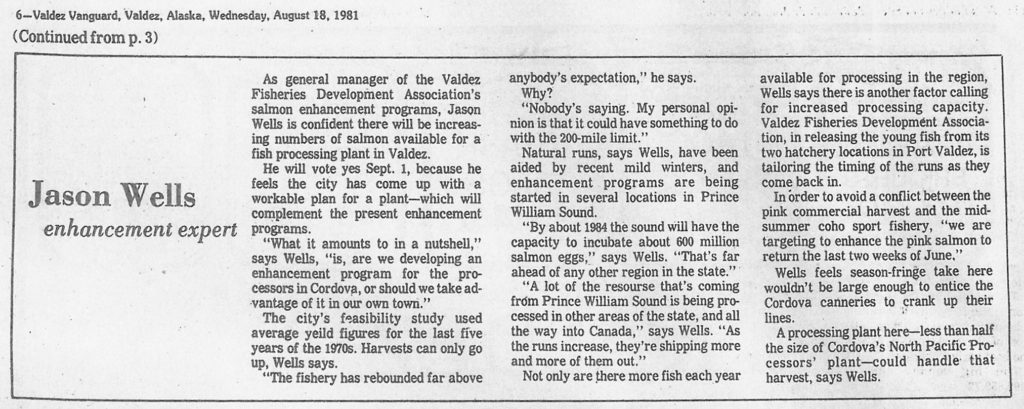

06/24/2020 – Interview with Jason Wells, Former VFDA Director

“I told him that we’d have to be fools not to try” : A discussion with former VFDA director, Jason Wells

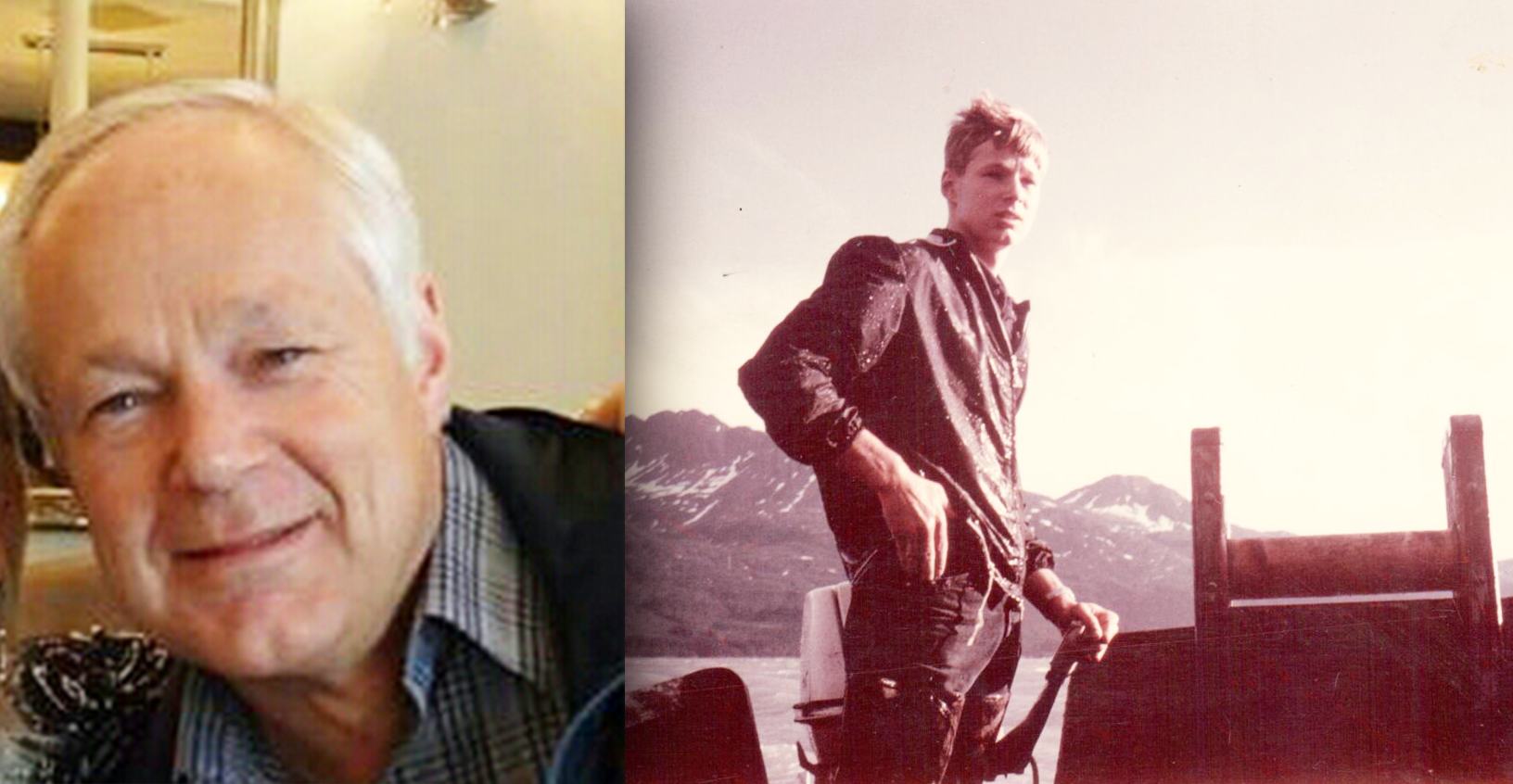

Jason Wells, former VFDA Director

Jason Wells, former VFDA Director

Can you talk about who you are and your background?

“My name is Jason Wells, and I was born in Fairbanks, AK. I went to Valdez in 1952 when I was about 4 years old. I spent most of my adult life there.”

Can you talk about your connection to commercial fishing?

“I started my first commercial fishing job in 1951. I was thirteen years old and unloading tenders for a cannery in Valdez run by Tom Jatzek. The following year my dad bought his 30ft seine boat, so by the time I was 14 years old I was the deckhand. That was a big job, but it was a different fishery then.”

What is unique about experiencing Alaska as a commercial fisherman? Did it offer a special connection to your work at VFDA?

“The most important thing about commercial fishing was that we could go to work at a very young age with our families. We learned how to work and be responsible when we were 14, 15 years old.”

Do you feel like having that responsibility and that work ethic helped you when you guys decided to found VFDA?

“My interest in hatcheries started when I was in sixth or seventh grade. The ADF&G guys used to come over from Cordova to Valdez and borrow my dad’s pickup truck–we had a hardware store in Valdez–and they’d go out into the stream fry sampling, and I would go with them. Later on, I would make their coffee and sit around and listen to them talk about hatcheries. This was right after statehood, so this would be Wally Noerenberg and Ralph Pirtle.”

What was it when you were sitting around listening to them talk that made you excited about hatcheries?

“I would think about the potential of being able to protect the young fry when normally they’d be in the stream gravel, and to give them protection and a head start. Our life was pretty much around fish. When we were kids, we would go fishing in the sewer creek in old Valdez and grab fish out of the spawning stream. Catching them on hook and line. It was just about fish, so we kind of got started early.”

“It wasn’t until my second year in university at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, when they started the Private Nonprofit Hatchery Act (1974), that I moved my studies over to hatcheries. My last two and a half years I went down to the University of Washington and graduated in fisheries there.”

What as a biologist peaked your interest most in hatcheries?

“Two or three really bad seasons when the stream beds froze in the 1970s was not only the impetus for my interest, but it was also for the state of Alaska. Prior to that, there were no private hatcheries at all in Alaska–they were all state or federal–so this opened up an opportunity for the fishermen to really step in and do something for themselves.”

What did you feel was really unique about Alaska’s hatchery model in those early days?

“The first thing was that it was the first time in state history that private people could get involved in the hatchery program. The fact that they were not-for-profit made it a trust to enter into the hatchery program. They were basically running a public trust.”

Can you talk about the process of starting the hatchery program in Valdez and ultimately VFDA?

“There was an association started in 1977 or 1978 called Valdez Fisheries Association. They were trying to figure out what they could do with hatcheries, and I–by a set of circumstances–ended up in Valdez at that time and went to Cordova for a regional planning team meeting. I talked with some of the guys working closely with Alaska’s hatchery program, and they said if you want to do something, you need to hire someone who works specifically on developing the hatcheries. So I was hired in 1979, and shortly thereafter we changed the name to the Valdez Fisheries Development Association because we wanted to do more than just be a salmon hatchery; we wanted to develop fishery resources for our community.”

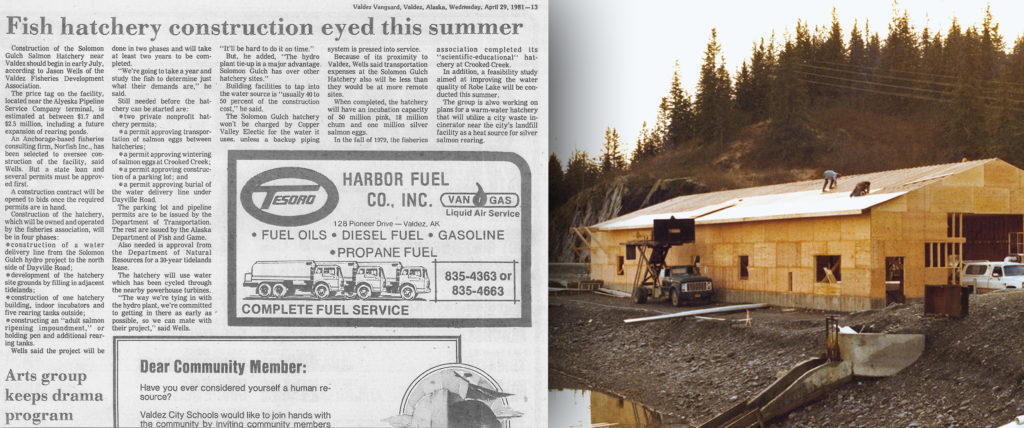

Crooked Creek Hatchery – 1981

Crooked Creek Hatchery – 1981

How was that received locally? Did you have to do a lot of education to help people understand?

“Yes, at that time hatcheries were a new entity, and no one had really heard of them besides the Armin F. Koernig hatchery. We had to convince not just the commercial fishermen that it would be to their benefit, but we had to convince the sports fishermen that an area could be opened up near town, and that it would work in their favor. It was a lot of politicking.”

Was there special education that you had to do within the region and up the road system?

“Because we have a separate watershed area, we didn’t have to work with any others so much–as we did with the sport fishermen. That’s why you find a large Coho component in our existing business plan.”

How long did you work with VFDA? Was it always in the same roles or different roles?

“I started out as the project manager in 1979 and worked in that capacity until about 1987. Then they made me the CEO. In 1991 I took a hiatus for 8 years, but I went back to work for them in 1999 and worked until I retired in 2012.”

What was the biggest challenge you overcame in the early days of developing the hatchery program? What were some of the most memorable challenges you overcame in the different roles you had when you were with VFDA?

“It was an unknown entity because we didn’t know if we could raise fish in Port Valdez and get them to come back. We didn’t know what the ocean survival would be and we didn’t know what the site location was. The first thing I did was to do a resource evaluation, and we built a small facility at Crooked Creek and ran that for a couple years starting in the fall of 1979. We had fishermen come out and built us a 16ft x 24 ft building that turned into an incubation building.”

“We got hands-on experience, and as we began looking at resources, the biggest issue we had was that we did not have any winter water reservoir. We learned that they were building the hydroelectric plant at Solomon Gulch, so it was a given that we had to try that. I had a guy from ADF&G tell me that we couldn’t raise fish in that silty water, and I told him that we’d have to be fools not to try. And we were still fools, but we made it work.”

Coho Rearing Building construction – 1982

Coho Rearing Building construction – 1982

“The biggest challenge, and the most fun of the entire process was to take the incubators we had at the time of the start, they would hold 5,000 eggs, and then we built some Kitoi boxes that could handle about 250,000 [eggs], but we only were doing 60,000,000 eggs to start with. So how do you scale up from an incubator that holds about 5,000 eggs to one that will hold 1.2 million eggs while keeping them alive? How do you handle them? How do you pick the dead eggs out of them? How do you do it in a cost-effect way? How do you keep the fungus out of the incubating trays? This was the fun part about it, to scale the process from doing 20 to 30 million eggs to doing hundreds of millions of eggs.”

Salmon Egg Incubator – Crooked Creek Hatchery (Left), “Super Incubators” – Solomon Gulch Hatchery (Right)

Salmon Egg Incubator – Crooked Creek Hatchery (Left), “Super Incubators” – Solomon Gulch Hatchery (Right)

Did you have to bring in any experts to help you solve those problems or was it all local innovation?

“We did both. We went to a fellow by the name of Harold Zenger from Juneau who helped develop the stackable incubator trays. We also built the ”Super Inc” , which was a four by four by four incubating box that we could eye about 4.5 million eggs in. It was also easier to clean. All of these things had to work en masse, and we had to be able to handle the out-migration of 230 or 270 million eggs in about a 2-3 week period. How do you do that without killing them? So we brought in tomato handling technology, and we were able to move the fry without damaging them.”

“The other thing was that the fish food, of the size needed for our pink salmon fry, was very recently put on the market by the farmed salmon industry. We had to bring that in and develop it so that you could feed all the fry mechanically. That was the fun part. And the challenge we had was that the site itself had about a quarter of a mile of mudflats before you get to the hatchery, so how do you move stuff across that, like fry and salt water? There were a lot of challenges.”

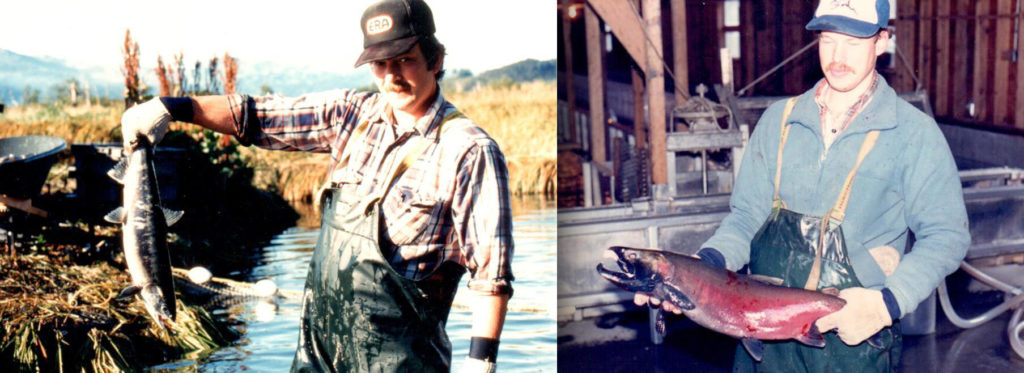

“Probably the most important thing we had was a lot of dedicated staff come on with the company. We were able to hire Paul McCollum out of Bethel, and Dave Cobb who was a fine guy and good worker, and they were able to put a staff together and do our remote egg takes. There were just a myriad of different parts of the puzzle that came together to make it work. Probably the most important part was that the state of Alaska, in 1974, developed a salmon enhancement revolving loan fund, so that gave us a pool of money to go after to put concrete in the ground.”

Fish Culturist, Dave Cobb conducting a remote egg take to seed Solomon Gulch Hatchery – Early 1980’s (Left), Hatchery Manager, Paul McCollum holding a Coho salmon for spawning – Early 1980’s (Right)

Fish Culturist, Dave Cobb conducting a remote egg take to seed Solomon Gulch Hatchery – Early 1980’s (Left), Hatchery Manager, Paul McCollum holding a Coho salmon for spawning – Early 1980’s (Right)

How do you move the fry across the flats?

“Ken Morgan, who was our hatchery manager until he retired, developed a system where he could pick up a whole tray and turn it upside down into a pool of water, and then we could separate the fish from the plastic substrate and clean it at the same time. You could do about 5 or 6 incubators an hour. Out of that pool of water, we picked the fry up with the tomato pump and moved it really slowly through a long hose out to the net pens.”

Outmigration Dump Tank created by Hatchery Manager, Ken Morgan

Outmigration Dump Tank created by Hatchery Manager, Ken Morgan

What helped you persevere through the difficult times of getting VFDA to scale and what was your inspiration during those times?

“I prayed a lot, and the Lord helped me and gave me a lot of good ideas and always helped me get out of a jam. And of course always having good staff and good hard workers who bought into the program 110%. They kept pushing and pushing and also lost a lot of sleep.”

“I think the impetus was once we saw in 1984, our first big return of fish to the hatchery. Steve Alley took his little boat out, the Steven Daniel, and he got 147,000 pounds of fish that he offloaded on the offshore tender. We kinda knew that at that point in time that we could do it. We could get ocean survival that was sustainable. That was very memorable, and I think my son has got a picture of that set on his wall at the hatchery.”

F/V Steven Daniel cost recovery set estimated to be 147,000 lbs of SGH Pink salmon – 1980’s

F/V Steven Daniel cost recovery set estimated to be 147,000 lbs of SGH Pink salmon – 1980’s

Was some of that inspiration tested or was it galvanized in ‘89 when the oil spill happened?

“We didn’t know which way the oil was going to go, so we stepped back a little bit because we knew there were places that were in greater need than us. The oil itself went to the southwest. I guess we went from a small mom-and-pop hatchery to one that knew we needed to keep our eye over our shoulder and be a little more diligent on procedures.”

Was there a renewed feeling of responsibility because you knew how the oil could impact wild stocks?

“Yes, I don’t recall too much other than we really got busy and used some of our equipment on the oil-spill cleanup. But we understood that Prince William Sound Aquaculture Corporation was in the throes of it more than we were, so we held back and gave them opportunities to make sure that their needs were met.”

Do you have any specific memories from over the years of specific ways you saw VFDA grow?

“We actually looked at it from the standpoint of what we could physically do. Once we made some assessment of that, we looked at how we could make VFDA financially sustainable. That’s when we started to grow the hatchery because, at 60 million eggs, if we had a bad year we couldn’t give anything to the fishermen. We decided to build the hatchery larger so that on a poor return year we could still pay for it and give the fishermen something to take home for their families.”

“The other thing was that when we started the hatchery, the only thing to do with the pink salmon was to put it in a can. The processors would put up about 3 million cases, and they’d walk away from the rest of the run while we were still producing more fish. We began to pursue product development with pink salmon, and between us and PWSAC, we brought in a filet expert Peter Kuttel, who put a lot of upward pressure on the price of fish. That really helped the industry–not just the fishermen but also the processors and the entire economy.”

What was your motivation in continuing VFDA?

“The first impetus was that we did not have a seine season in the sound during the early 70s. Once we got where we could see that we could get a good return, we began to see that we could financially come up with a way to do it. It was a matter of taking one step after another, and what we learned, we applied.”

How quickly did you see the number of fishermen scale in response to VFDA’s returns?

“I think it was in 1987 that we had our first 10 percent survival (5.7 million fish), and that was the turning point. The Valdez Arm has been different ever since.”

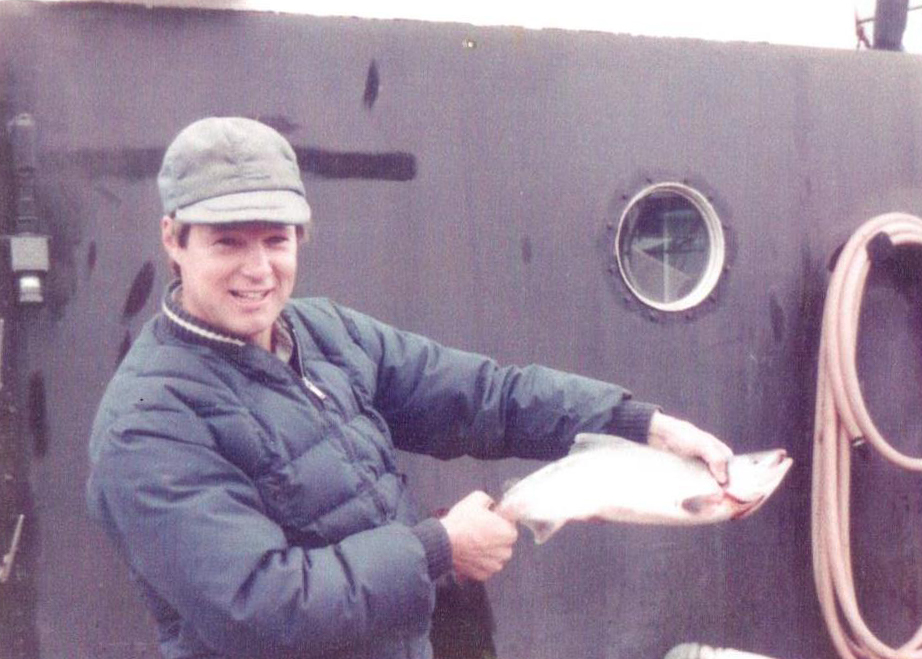

Jason Wells holding one of the first Pink salmon returning to Solomon Gulch Hatchery – Early 1980’s

Jason Wells holding one of the first Pink salmon returning to Solomon Gulch Hatchery – Early 1980’s

Why is VFDA important to commercial fishermen and other user groups?

“A lot of things happened in those years, and one of the things that happened was limited entry. It actually gave the fishermen ownership in the resources. Instead of a situation where you came, grabbed, and ran, now you had a vested interest in the industry because you owned a permit. The fishermen started treating fish and the management differently. They began to protect it more than they had previously.”

What role does VFDA play in the PWS region? What are your thoughts on the unique impacts that VFDA has on the fleets and different user groups? Including local economics.

“I use a measuring stick that is the number of boats that over winter in Port Valdez that are commercial seiners. When we first started VFDA, we had no processors in Valdez, besides a small mom-and-pop operation. We used to have 8-12 boats over winter in the harbor in Valdez, and here we are–40 years later–and we have almost 45 vessels which are, each and every one, small businesses of people who buy groceries and eat at restaurants. They buy their fuel and recreate in our port while they get their boats ready. It’s added a lot of activity to our harbor.”

“Of course, the silver salmon derby has changed from where you had to go find your fish to now. When they’re running, you can really get your limit in half a day. The economic impact of VFDA to our community is pretty astounding.”

Common Property seine opener at Solomon Gulch – Early 1980’s

Common Property seine opener at Solomon Gulch – Early 1980’s

Do you have any final thoughts on the greatest contribution VFDA has made in the last 40 years to the region?

“I think it’s primarily, and to a large degree, it’s a little difficult to definitely say it, but a majority of the time commercial fishermen and sports fishermen get along pretty well. We built a management structure that is good for both of them. We produced about a 100-200 thousand Coho for the sport fishing industry. There’s a little bit of animosity, but at least we get along pretty well.”

If you had to boil it down, what do you think VFDA’s greatest achievement is?

“I think the greatest achievement is that we took a resource of winter water flow, through the Solomon Gulch Hatchery, and we married that resource with the amazing ability of the salmon to come back to its native spawning stream. When we did that, it manifested in great abundance. That’s really the beauty of it.”

What is your highest hope for the next 40 years of VFDA’s operation?

“We’ve tried a number of things, like developing a Chinook program that never really took hold, and I’d like to see that happen. I’d like to see the hatchery programs get some credit because for 40 years we’ve seen fish returning, and they’re still coming back. Man set his hand to them and didn’t destroy them, and they are not contaminated fish. I think there’s a lot of agenda-driven science, and I’d like to see some of that go over the hill.”

“I’d like to give a shout out to the community of Valdez over the years. A lot of the original board of directors have gone on ahead of us, and even a lot of the guys I fished with have either passed away, or are no longer in the industry, but they were critical contributors with their good nature and willingness to work together. It’s not very often that you get to see that in a community. Even the sport fishermen coming in and supporting us, we couldn’t have done it without our community.”